In today’s world of numeric script, choices like adding a slash through a zero, serifs to a one, or a cross through a 7 appear to be predominantly stylistic and determined by personal preference and learned practice. However, examining the origin of the Arabic numeric system reveals a more complex truth—that there was once a single “correct” way in which numbers were written.

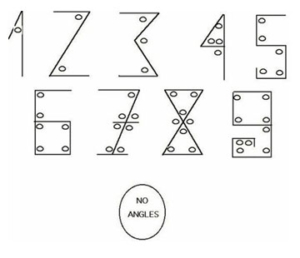

The foundation of the Arabic numeric script was derived from a basic geometric principle, in which the representation of each number contained the same number of fully enclosed or semi-enclosed angles as the valuation of the number. The diagram below details this idea:

Original Arabic numeral scripts. The image denotes the location of “counted” angles with small circles on the interior of the numerals.

Here, the seven’s script has not one, but two horizontal lines intersecting the angular vertical line of the character, solely for the purpose of containing seven angles within the geometry of the number.

However, the seven is not the only number written in a different manner than modern script dictates. Numbers usually characterized by curvature, such as the ‘2’, ‘3’, ‘5’, ‘6’, ‘8’, and ‘9’ have all been linearized, and are all composed of only straight lines. This follows the logic put forth earlier, and allows the script of each numeral to contain exactly as many angles as the numeral’s value.

The zero is the only number within the set that has a curve, as it needs to lack any angular geometry whatsoever. This is achieved with the same oval shape we use to write zero today.

Many people today argue that the line across the seven is primarily used as a means of distinguishing it from the number ‘1’, which can sometimes look similar in script. This is found more dominantly in Europe, as it is customary to write the number ‘1’ with the small serif at the top. The same argument justifies lines like the slash across a zero, as a means of distinguishing it from the letter ‘O’. In today’s world, these reasons for varied scripts are just as valid as the historical precedent.

There is a rich history behind small gestures like crossing sevens. In modern practice, however, such choices are often a product of stylistic choice and vary between individuals and geographic locations.